Christina Gutierrez-Dennehy

We addeHis Revels Now are Ended—Re-Imagining The Tempest for 2021

I have always been drawn to The Tempest. In fact, it was the first play by Shakespeare that I read (at the tender age of 10), and the one that drew me into an exploration of the magic of Shakespeare’s theatre—an exploration that 10-year-old me had no idea would become my career.

As I came to understand over years of work with both historical texts and contemporary American contexts, however, while there is indeed magic in The Tempest there is also deep pain. The play easily forgives—if not outright celebrates—the role of the colonizer. Exiled from his Italian home to the shores of a mysterious island, Prospero very quickly recreates hierarchical European systems of power, subjugating the island’s indigenous inhabitants to his own ends. Written at a time when England was becoming a formidable colonial power, The Tempest stages burgeoning English notions of whiteness and racial difference, ultimately vindicating its European characters while damaging its native ones.

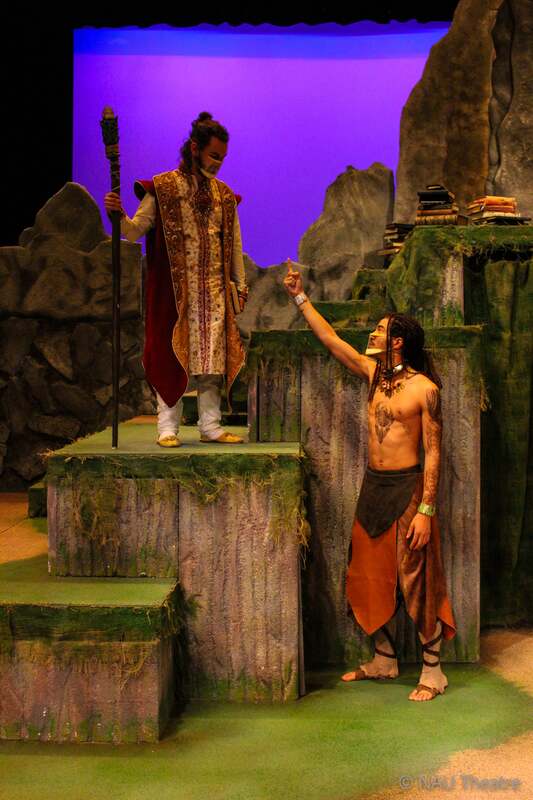

Although the magic of The Tempest creates an opportunity to celebrate the unique alchemy that comes from the interaction of performers and audience, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic forced an 18-month pause in live performance, I knew from the start that if we were going to do this play we had to address its problematic elements. The pandemic provided space and time for theatres to think about their impact in national conversations about race, power, and representation, and to begin to address harmful practices of the past. The work of NAU Theatre was no exception. Our Tempest used Shakespeare’s text to center the voices of the indigenous islanders, casting doubt on Prospero’s development throughout the story. We retained the magic of the text, but located it in the island itself—a place “full of noises” which eventually triumphs over the imported books from which Prospero derives his power. Inherent in this newly anti-colonialist story were the same moments of beauty, wonder, and humor that fill Shakespeare’s original tale, but our sympathies lay with the subjugated Caliban and Ariel rather than the aging Prospero. We added a prologue in which Caliban rescues the injured Prospero, and then gave the play's famous epilogue to Caliban rather than Prospero.

The Tempest is often touted as a story of forgiveness, a characterization that refers chiefly to Prospero’s capacity to forgive the other European characters who have wronged him. Given the violence Prospero wrecks on the island, however, we were not telling this story of forgiveness . Rather, our tale was one of reclamation. We began and ended not with Prospero, but with Caliban. As Prospero and the other European characters depart the island, we saw power shift back to the islanders. They have been changed irreparably, but we can only hope that a process of healing had begun. As our country begins its own process of healing—a process that demands introspection, humility, and often radical change, I hope that we can find in Shakespeare’s magic the seeds of our own growth.

I have always been drawn to The Tempest. In fact, it was the first play by Shakespeare that I read (at the tender age of 10), and the one that drew me into an exploration of the magic of Shakespeare’s theatre—an exploration that 10-year-old me had no idea would become my career.

As I came to understand over years of work with both historical texts and contemporary American contexts, however, while there is indeed magic in The Tempest there is also deep pain. The play easily forgives—if not outright celebrates—the role of the colonizer. Exiled from his Italian home to the shores of a mysterious island, Prospero very quickly recreates hierarchical European systems of power, subjugating the island’s indigenous inhabitants to his own ends. Written at a time when England was becoming a formidable colonial power, The Tempest stages burgeoning English notions of whiteness and racial difference, ultimately vindicating its European characters while damaging its native ones.

Although the magic of The Tempest creates an opportunity to celebrate the unique alchemy that comes from the interaction of performers and audience, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic forced an 18-month pause in live performance, I knew from the start that if we were going to do this play we had to address its problematic elements. The pandemic provided space and time for theatres to think about their impact in national conversations about race, power, and representation, and to begin to address harmful practices of the past. The work of NAU Theatre was no exception. Our Tempest used Shakespeare’s text to center the voices of the indigenous islanders, casting doubt on Prospero’s development throughout the story. We retained the magic of the text, but located it in the island itself—a place “full of noises” which eventually triumphs over the imported books from which Prospero derives his power. Inherent in this newly anti-colonialist story were the same moments of beauty, wonder, and humor that fill Shakespeare’s original tale, but our sympathies lay with the subjugated Caliban and Ariel rather than the aging Prospero. We added a prologue in which Caliban rescues the injured Prospero, and then gave the play's famous epilogue to Caliban rather than Prospero.

The Tempest is often touted as a story of forgiveness, a characterization that refers chiefly to Prospero’s capacity to forgive the other European characters who have wronged him. Given the violence Prospero wrecks on the island, however, we were not telling this story of forgiveness . Rather, our tale was one of reclamation. We began and ended not with Prospero, but with Caliban. As Prospero and the other European characters depart the island, we saw power shift back to the islanders. They have been changed irreparably, but we can only hope that a process of healing had begun. As our country begins its own process of healing—a process that demands introspection, humility, and often radical change, I hope that we can find in Shakespeare’s magic the seeds of our own growth.